Censo

Given America’s bedrock belief in the right to privacy and individual freedoms, answering questions for the Census has always raised questions by some who are concerned that the government may be intruding too much into people’s lives.

Petaluma has been participating in census taking since 1850, the year California became a state. That first survey, a copy of which resides in the Petaluma History Room consists of twelve randomly numbered pages, and lists residents who came to Petaluma from all over the world, including England, Peru, Mexico, the Sandwich Islands, Switzerland, and a number of American states. Most of the occupations listed are farmer, laborer, clerk, or merchant.

The fifteen national censuses undertaken every decade since are critical to businesses, government, and other organizations that rely on census information for decision-making and community design. The Argus-Courier and its predecessors provide a wonderful view into the concerns and reasons for taking part in the census. In 1910, the Petaluma Argus encouraged everyone to participate and noting that: “there’s nothing in it for the Argus except that it takes pride in this city and in getting all that is coming in population as well as in other matters.”

Concern that everyone be counted prompted the Argus-Courier to continue to encourage participation by inviting readers who might not know where or how to get counted to contact the paper; which would connect them to the proper folks.

May 13, 1910

Why did they think it was important to be counted? Because in December of 1910, after the count came in, California was awarded four new seats in the U.S. Congress. More congressional seats equaled more political power for a growing state, made possible thanks to the census.

Dec 2, 1910

The newspaper also offered this advice: “Don’t be suspicious or ‘cagey’ in your answers. Give the facts, even if they seem personal. They will be held in confidence and not used against you.”

Questions about the kinds of questions included in the census are as old as the census itself.

“It’s getting to the point,” the Argus-Courier reported a senator from Pennsylvania saying in 1940, “where a housewife will have to account for her pots and pans and a man will have to take inventory of his tackle.” That same year, President Franklin Roosevelt went out of his way to reassure citizens “there need be no fear that any disclosure will be made regarding any individual person or his affairs.”

There is always the issue of the census takers. Petaluma’s 1850 census contains a footnote that states: “The 1850 census-taker was an extremely inaccurate man who took no time to get the correct spelling of names and his handwriting in many instances is illegible.”

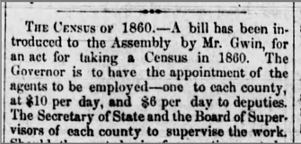

Two issues in attracting census takers since the beginning have been money and proper aptitude. In 1860, census takers earned a lucrative $10 a day, or roughly $290 in today’s currency (approximagely $34 per hour for an eight-hour day).

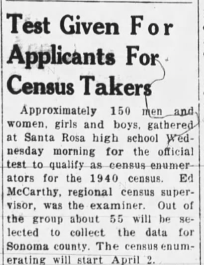

To be more selective in hiring local census takers, in 1940, a test was administered for 150 aspiring census takers, of which 55 were ultimately chosen.

Sonoma County Journal

Jan 27, 1860

Sonoma County Journal

Jan 27, 1860

Likewise, in 1980, prospective census workers in Petaluma needed to pass a test for positions that started at an hourly rate of $3.50, or $11 in today’s currency:

In the 1930s, when Petaluma was still largely rural, the Argus-Courier encouraged everyone who lived on a farm to remember the census taker might be frightened away by barking dogs. “When the census taker calls,” the editor recommended, “tie your dog and greet your visitor with a smile. He is just a hard working emissary of Uncle Sam. And a human being to boot.”

It also offered some advice for census takers who turned up during supper time:

While most of the data captured and used in a census pertain to issues of the day, for historians, genealogists, and others interested in finding information on their family roots, information collected in census records is critical. This year’s census, like those before it, will help future generations in understanding our lives today.

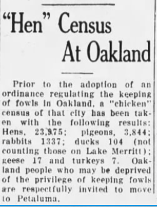

On that score, while it was not a part of the official U.S. Census, during the 1930 census in Oakland, a proposed local ordinance outlawing the private ownership of chickens and other fowl led to the city conducting a “hen census.” I thought that their conclusion was pretty spot on:

March15, 1930

Apr. 2, 1930